2013/02/13

リスク対策ドットコム英語版>記事

8. Medical professionals and groups such as the Japan Disaster Medical

Assistance Teams (JDMAT’s), the Japan Medical Association Teams

(JMAT’s), Humanitarian Medical Assistance (HuMA) Teams, and others quickly went to the disaster area to provide assistance. 9. Prefectures and municipalities from across Japan sent teams of staff to the stricken areas to assist the survivors. 10. Numerous Non-Profit Organizations (NPO’s) and individual volunteers contributed significantly to the relief effort. In many cases, ordinary people simply quit their jobs and went to Tohoku to provide help. 11. Donations poured in from around Japan as well as from foreign countries. These and other activities reflect a Japan where professionalism is high and where the volunteer spirit is more strongly present than many people may have thought. Even today, nearly a year later, countless individuals are working to help alleviate the suffering of the disaster survivors. However, I also found the following shortfalls: 1. The Government of Japan lacks a comprehensive and realistic plan for responding to large disasters. The Japan Government’s disaster response plan actually seems to consist of numerous government agency plans that are unrelated to each other. In many cases these plans failed to address or even acknowledge problems that were occurring in the field. In part, this is because the government also lacks trained, experienced disaster response professionals. As a result, the government’s response to the March 11 disaster was poorly managed and coordinated, and many people suffered needlessly. For example: ● Valuable commodities such as food and medicine were often delivered to locations where they were not needed, while survivors at other locations suffered shortages. ● In some cases, much-needed donations were turned away due to the government’s inability to receive and manage donations.●

Requests from medical staff in the field for urgently-needed help went unanswered. These and other problems were consistently reported to me in the course of the research. Some of these problems are discussed in greater detail in the findings below. 2. The lack of comprehensive, realistic disaster response planning also extends to many Japanese cities and prefectures. Although prefectural and municipal officials and staff in Japan are expected to deal with disasters, they receive almost no training in disaster response from the National Government. As a result, many local officials did not know what to do in the disaster and, while doing their best, often were unable to properly assess or meet local needs. Prefectural staff were also often described by responders as “doing their best,” but not being very effective due to their lack of disaster knowledge or training. 3. The lack of a uniform incident management system in Japan added to the confusion and poor use of resources. Large-scale disaster response is a complex endeavor that requires extensive management. Many of the responders I spoke with told of having to invent their own management systems in the midst of the disaster to try to coordinate the activities of multiple jurisdictions who were delivering multiple services to a huge and diverse group of survivors who were themselves widely scattered in shelters across the disaster-stricken area. While the responders are to be commended for devising management systems in the midst of disaster, this does not seem to me to be the best way a response should be managed. 4. The full potential of volunteers, donations, and Non-Profit Organizations (NPO’s) was not utilized effectively by the government. The government did not appear to have a plan for incorporating NPO’s or donations management into the disaster response. As a result, NPO’s received little or no advice from the government as to what was needed or where, and were left to their own devices (and personal connections) to send aid into the disaster area. Donations of critical items such as food were turned away by the government at the very time when many of the survivors were desperately in need. On the other hand, unneeded donations poured into some areas, resulting in oversupplies of food and medicine in some areas while other areas faced shortages. 5. Communication between the Government and the field responders seemed to go in one direction only, that is, from the top down. Field responders such as medical doctors, pharmacists, and public health specialists at the disaster sites lacked an effective means to notify the government of their requirements. Instead, the government appears to have relied in large part on the news media for information regarding the disaster conditions. This lack of communication and accurate information resulted in the government’s often being completely unaware and/or misinformed as to what was needed in the field, leading to a misallocation of resources such as food and medicine as cited in item #4, above. 6. Shelter management in the disaster-stricken areas was weak and inconsistent, and in some cases appeared to be nearly nonexistent. Many shelters were described as either being “self-managed” or “no management.” Local residents often did their best to manage local shelters in the absence of any government presence or any guidance on shelter management. The result was a very uneven level of management, where some shelters were very well-run and others were not. 7. Nutritional needs of the disaster survivors were met very poorly, often consisting only of some rice, bread, and water daily. This poor nutrition, when combined with the already-weakened condition of many of the survivors, resulted in additional illnesses and medical needs among the survivors that in all likelihood could have been avoided by simple nutritional planning. Some doctors feel that this nutritional deficit may have contributed to fatalities among the survivors, especially the elderly. There did not appear to be any effective plan for meeting the nutritional needs of the disaster survivors. 8. The government may be overly-relying on the Japan Self Defense Force (JSDF) in disaster relief. The JSDF was quickly mobilized and dispatched in large numbers on March 11 and in the days that followed. This willingness to utilize JSDF, and JSDF’s ability to respond quickly, is an enormous benefit to Japan’s disaster response capability. However, it also carries the risk of over-reliance on JSDF to the detriment of broader government-wide disaster response planning. It is also questionable as to whether the JSDF by itself has sufficient resources to address the full range of disaster response planning in such areas as nutritional planning, shelter management, public health, communications, and others listed in Recommendation #3, below. 9. As a result of the above issues, many individual groups are developing their own disaster response plans independent of the Japan Government. Many of the responders and organizations I spoke with are tired of waiting for the government to address their concerns, and are beginning to develop their own independent plans for future disasters. While this is fully understandable given the problems that occurred in last year’s disaster response, it would also seem likely that a proliferation of separate and unrelated disaster response plans will add to the confusion in future disasters. On the other hand, if the government can reach out and include these groups in developing a comprehensive response plan, the result could be a greatly-strengthened disaster response system. 10. Japan has a wealth of skilled disaster response professionals, but nearly all of this skill lies outside of either the Cabinet Secretariat or the Cabinet Office for Disaster Management, the two Japan Government offices nominally in charge of managing the response to large disasters. Staff who I met from the Cabinet Secretariat and the Cabinet Office for Disaster Management seemed uniformly bright, dedicated, and hard-working, but rarely did either they or their leaders appear to have much experience with disasters, and those staff members who gained experience in last year’s disaster will soon rotate away to other jobs. One box on the Cabinet Secretariat’s organization chart is labeled “Expert Committee for Responses to Situations,” but in fact appears to consist not of “experts” but just high-ranking political officials. Most true disaster experts I met in Japan were either in the JSDF, the fire service, the health and medical professions, or non-profit organizations, but the Japan Government did not appear to be drawing upon this expertise to strengthen its disaster response plans. 11. Perhaps worst of all, there does not seem to be any feedback mechanism to take lessons learned from this disaster to improve preparedness for future such events, which unfortunately are likely to occur given Japan’s level of risk to disaster. While the Japan Government may tinker with some of the details, I did not see or hear of any effort to comprehensively address the issues outlined above. Recommendations Based on my research, I would make the following seven recommendations to the Japan Government: 1. Learn from the experience of the Japan’s disaster responders and experts. During my 46-day visit to Japan under the JSPS Fellowship, I spoke with numerous disaster responders and disaster experts and, as shown above, heard many stories of the successes and failures of the earthquake/tsunami disaster response. However, in the course of 20 lectures and 28 interviews, I cannot recall anyone telling me that the Japan Government has asked for their opinions or inputs as to how to strengthen the response for future disasters. If I, as a visiting foreigner with limited Japanese language skills, can obtain so much information in the space of 46 days, surely the Japan Government could do even better. I strongly recommend that the Japan Government make an intensive effort to reach out to the many disaster responders and experts in Japan and learn from them what needs to be done to strengthen Japan’s ability to respond effectively to future disasters. 2. Put someone in charge of disaster response planning and the response itself. As it now stands, no one person or agency in the Japan Government is really in charge of disaster response planning. The responsibility is spread out among numerous staff and officials who continuously come and go. With no one person in charge of disaster response planning, no one person is credibly in charge of the disaster response either, and we are left with the Prime Minister of Japan himself shouting orders into a phone during the disaster. Whatever qualities the Prime Minister may have, it is unlikely that he will be a professional disaster response manager, nor should he be. The government needs to have a full-time disaster manager (with staff) who is knowledgeable in the field of disaster management and who is empowered to develop a strong disaster response system for Japan. 3. Get away from hazard-specific planning, go to all-hazard planning. The Japan Government still uses “hazard-specific” disaster planning, that is, one plan for an earthquake, another for a tsunami, another for a terrorist incident, and so forth. From my experience, that approach is badly outmoded and leads to confusing and impractical plans as well as numerous gaps in the response. I recommend instead that the Japan Government adopt the “all-hazard” approach, whereby plans are categorized not by type of disaster but by mechanism of the disaster response, for example*: 1. Transportation 2. Communications 3. Public Works and Engineering 4. Firefighting 5. Emergency Management 6. Mass Care, Emergency Assistance, Housing, and Human Services 7. Logistics Management and Resource Support 8. Public Health and Medical Services 9. Search and Rescue 10. Oil and Hazardous Materials Response 11. Agriculture and Natural Resources 12. Energy 13. Public Safety and Security 14. Long-Term Community Recovery 15. External Affairs * Source: National Response Framework, US Dept. of Homeland Security/FEMA Then, each of these 15 categories (called “emergency support functions”) is assigned to the government agency or NPO most suited to that particular function. Taking #8, “Public Health and Medical Services” as just one example of the difference: Using the “hazard-specific” approach, the Japan Government’s decision to have the Japan Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (JDMAT’s) prepare exclusively for a scenario similar to the Hanshin Earthquake left these same JDMAT’s ready for treating the trauma injuries from an earthquake but poorly prepared and equipped for the many health and medical problems that occurred after the tsunami. In contrast to this, an “all-hazard” approach would instead put the Health Ministry in charge of developing a comprehensive approach to dealing with health and medical problems and issues that could arise in a full range of disaster scenarios, including, for example: ● traumatic injury, ● hypothermia, ● public health, ● environmental health, ● mental health, ● pharmaceutical needs, ● special needs/disabilities, and ● other. This same all-hazard approach could be applied to each of the 15 disaster response categories shown above. No planning approach is perfect, but the all-hazard approach would go a long way in ensuring that a full range of disaster-related problems are considered and planned for ahead of time. 4. Develop a comprehensive and realistic national disaster response plan. As noted above, the Japan Government’s disaster response plan actually seems to consist of numerous government agency plans that are unrelated to each other. In many cases these plans fail badly to address the actual problems that occur in disasters. For example, one physician in Tohoku told me that, during the disaster response, he was attempting to deal with a serious health problem involving disaster survivors who may have ingested dangerous chemicals from the tsunami waters. But when the physician tried to get help or advice from the government, he learned that three separate offices of the Health Ministry (back in Tokyo) had jurisdiction over the problem…and that it would be up to him, the physician in Tohoku, to try to somehow get an answer out of the three separate offices in the midst of his own disaster relief work! A comprehensive and realistic plan is one which includes all of the disaster-related issues listed in Recommendation #3, above, which includes all relevant government agencies and NPO’s, and which honestly addresses the types of problems that occur in disasters and proposes realistic solutions to these problems. 5. Implement a national incident management system such as the National Incident Management System (NIMS) that is used in the U.S. “Incident management” sounds like an abstract concept, but it is a very real problem in a disaster. Large-scale disaster response is a complex endeavor that requires extensive management. A lack of management can mean, for example, that some towns will be over-supplied with relief while other towns are neglected. March 11 responders I spoke with told of having to invent their own management systems in the midst of the disaster to try to coordinate the activities of multiple jurisdictions who were delivering multiple services to a huge and diverse group of survivors who were themselves widely scattered in shelters across the disaster-stricken area. How to prioritize needs? How to ensure that all geographic locations have been reached? How to avoid duplication of effort and misallocation of resources? The middle of a disaster response is not the time and place to try to invent a system to address these and other crucial questions. I believe that a nationally-accepted incident management system is badly needed in Japan, and I suggest as a starting point to consider existing systems such as the U.S. NIMS. 6. Train and professionalize emergency managers at all levels in Japan. Under the current system, Japanese emergency managers are generally individuals with little or no experience or training in emergency management. They are assigned to emergency management offices only temporarily, rotating in and out of their jobs every two years or so. It is baffling to me that a modern country like Japan would resist professionalism and training in such a crucial area. If I were going to a hospital for life-saving surgery, I would not want the surgeons to be a group of individuals with no training or experience in surgery, so why should such a lack of training and experience be applied to a critical field like disaster management? Given the high risk that Japan faces from earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes, and a host of other hazards, it seems to me that Japan needs to build a cadre of trained, experienced emergency managers at the national, prefectural, and municipal levels, as well as in the non-government sectors, to help face the next crisis. As noted in finding #10, above, Japan actually has a large body of disaster experts on which it could draw to provide the leadership and knowledge required to accomplish this goal. 7. Plan for the role of NPO’s, volunteers, and donations in disaster response. Voluntary support and donations for disaster survivors can be a major contribution to disaster relief if planned for ahead of time. But if not planned for, then volunteers and donations are instead often seen by government agencies as a burden or a distraction to be turned away, as so often happened in 2011. As cited in finding #4, above, NPO’s received little or no advice from the government as to what was needed or where, and were left to their own devices (and personal connections) to send aid into the disaster area. Donations of critical items such as food were turned away by the government at the very time when many of the survivors were desperately in need. On the other hand, unneeded donations poured into some areas, resulting in oversupplies of food and medicine in some areas while other areas faced shortages. Instead of turning away these important resources, or instead of using them haphazardly with no plan, I recommend that government agencies at all levels in Japan begin now to plan how to incorporate and utilize NPO’s, volunteers, and donations more effectively in future disasters. Conclusion Japan is a country that is at risk from numerous natural hazards such as earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes, and others. In addition to natural disasters, Japan also faces the risk of technological and industrial disasters such as chemical spills, nuclear accidents, large transportation accidents, and others. And like many other countries today, Japan faces the constant risk of terrorist incident or enemy attack. Fortunately, Japan also has a wide range of resources to deal with disasters. Specifically: ● Japan is a wealthy, modern industrial country that can afford to protect itself from disasters, and to respond should a disaster occur. ●Japan is a democracy whose government is ultimately accountable to the people. ●Japan has numerous and highly-experienced disaster experts who could contribute to building a stronger disaster response system. ●Perhaps most importantly, Japan is a strong society whose members are willing to help each other in time of emergency.The March, 2011 disasterwas catastrophic, and would challenge even the best-planned response system. However, saying that a disaster is catastrophic and challenging should not be an excuse to neglect disaster response planning; rather, it should be an incentive to make such planning as realistic and effective as possible to deal with future large disasters should they occur.

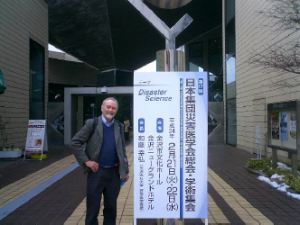

I hope this report may be helpful to my friends and colleagues in Japan to protect themselves and their country against disasters that may occur in the future. *** Researcher’s Background: I served as an Emergency Management Specialist with the US Government’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in Washington, DC from 1979 until my retirement in 2008. In that capacity, I helped to plan for and respond to numerous disasters such as earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, and terrorist incidents. I began visiting Japan as a lecturer in emergency management in 1996. In 1999, I was accepted into the Mike Mansfield Fellowship Program in Washington, DC. Under this program, I studied Japanese in Washington for one year (1999-2000) and then spent one year in Tokyo (2000-2001) where I studied Japanese emergency management systems. At the end of my year in Japan, I wrote a research paper entitled, “Emergency Management in Japan.” This paper was translated into Japanese and published in Japan in the journal Rescue, November, 2001. A short version of my report was published in English in the US by the Mansfield Foundation in the journal Asia Perspectives, Spring, 2002. I returned to the US in 2001, and since then I have been a frequent lecturer in Japan on the topic of emergency management. In 2009, I co-authored the chapter on the Incident Command System (ICS) for the Japanese Textbook of Disaster Medicine, and in March, 2011, an article I had previously written was included as a chapter for the new edition of Prof. Shunsuke Mutai’s book, Takameyo! Bousai-ryoku (“Strengthen Emergency Management!”). In August, 2011, I was awarded an Invitational Fellowship for Research in Japan by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), which enabled me to write this report. Disclaimer: This project was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and by Kanagawa University. However, the findings and recommendations reflect my own views only, and are not necessarily the views of either JSPS or of Kanagawa University. Limits of Study: My experience is mainly in the general area of disaster response planning, not in the specific area of nuclear safety. Therefore, the following report focuses on the response to the March 11, 2011 earthquake/tsunami disaster, not the issues of the Fukushima nuclear power plant.●This article was translated into Japanese and published on magazine "Risk-taisaku.com" vol.32.

◆Profile Leo Bosner is an emergency management expert with 30 years experience in the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), from which he retired in 2008. He had been actively involved in the government's emergency response to numerous disasters such as floods, wildfires, hurricanes, earthquakes, and terrorist bombings. Much of his experience includes analyzing emergency management issues and developing plans to address them. Between 1999 and 2001, he was a Mansfield Fellow spending one year in Tokyo, Japan, researching and lecturing on emergency management. His research report Emergency Management in Japan (in English) was translated and published in Japanese, and continues to be used as a reference work in Japan.Comments and Questions may be sent to him at Leobosner@hotmail.com.

リスク対策ドットコム英語版>記事の他の記事

- An ‘App’ for everything; But can Apps for Disaster save lives?

- Once upon a time in Fukushima

- UK experience of the Impact of Volcanic Eruptions

- BS25999 Certification Is No Guarantee of a Robust, Fit-for-purpose Business Continuity Capability

- A need to re-think the trade-off between continuity and productivity

おすすめ記事

-

-

-

-

-

中澤・木村が斬る!今週のニュース解説

毎週火曜日(平日のみ)朝9時~、リスク対策.com編集長 中澤幸介と兵庫県立大学教授 木村玲欧氏(心理学・危機管理学)が今週注目のニュースを短く、わかりやすく解説します。

2025/12/09

-

-

-

-

リスク対策.PROライト会員用ダウンロードページ

リスク対策.PROライト会員はこちらのページから最新号をダウンロードできます。

2025/12/05

-

競争と協業が同居するサプライチェーンリスクの適切な分配が全体の成長につながる

予期せぬ事態に備えた、サプライチェーン全体のリスクマネジメントが不可欠となっている。深刻な被害を与えるのは、地震や水害のような自然災害に限ったことではない。パンデミックやサイバー攻撃、そして国際政治の緊張もまた、物流の停滞や原材料不足を引き起こし、サプライチェーンに大きく影響する。名古屋市立大学教授の下野由貴氏によれば、協業によるサプライチェーン全体でのリスク分散が、各企業の成長につながるという。サプライチェーンにおけるリスクマネジメントはどうあるべきかを下野氏に聞いた。

2025/12/04

![2022年下半期リスクマネジメント・BCP事例集[永久保存版]](https://risk.ismcdn.jp/mwimgs/8/2/160wm/img_8265ba4dd7d348cb1445778f13da5c6a149038.png)

※スパム投稿防止のためコメントは編集部の承認制となっておりますが、いただいたコメントは原則、すべて掲載いたします。

※個人情報は入力しないようご注意ください。

» パスワードをお忘れの方